And just like that, we’re back to the usual winter programming! I’m very excited for the snow, however I could do without the sub-freezing temperatures. On the mornings where the thermostat in my car reads -5oF on my drive in, I often think about all of the wildlife (and plants) that must cope without the comforts of heated seats and woodstoves. Of course, they have countless physical and behavioral adaptations that allow them to survive. Every morning the sun rises on a new mosaic of tracks crisscrossing my backyard, letting me know that the local deer, squirrels, and four-legged predators continue to thrive despite the cold.

This Week on Tech Tip Tuesday

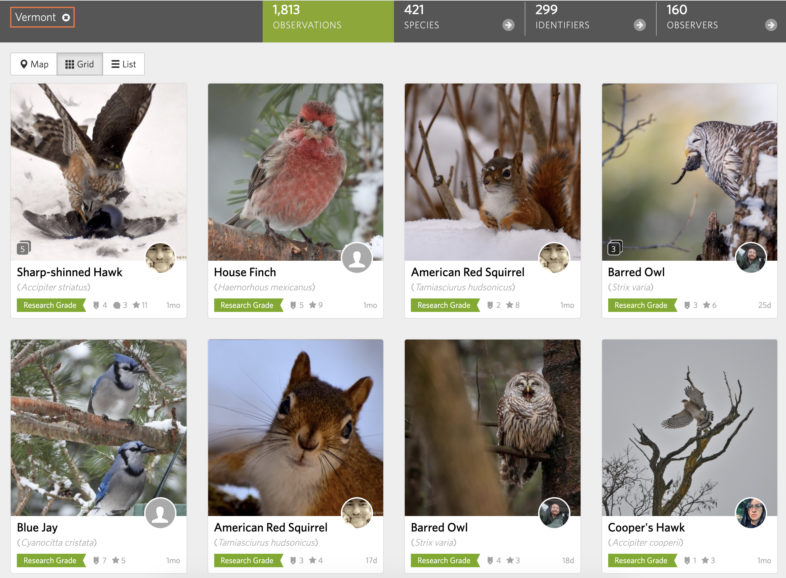

If this cold snap has you in hibernation mode, then this tech tip will be right up your alley. This week we’re talking about the identify tool. Now, I know that many of you have probably been putting your substantial naturalist skills to good use from the beginning of your iNaturalist adventure – after all, helping other users identify their cool finds is half the fun! However, not everyone is familiar with the time-saving wonders of the Identify tool.

How is it different than the way many of us approach identifying observations? Instead of going to “Explore”, searching for observations that “need IDs”, and clicking in and out of observations, using “Identify” allows you to use simple strokes to agree, add comments, and flip to the next observation. This means that you get to avoid the headaches caused by hitting “back” to get off a page, only to find that you’ve lost your place.

To get to the Identify tool, click on “Identify” along the top menu bar. Once you get to the page, enter the species and/or place you’re interested in identifying observations for. One neat aspect of Identify is the number of filtering options that exist. To explore these, click “Filters” to the right of “Go” next to the search bars. Once “Filters” is open, click on “More Filters” in the bottom left-hand corner to see the full range of options. Here are a few that you may find most interesting to play with:

1. Observations identified as unknown. To filter for observations marked as “Unknown”, go to the “Categories” section and click on the last option – a leaf outlined by a dotted line with a question mark in the middle. By isolating the “Unknown” observations, you can easily go through and add broad identifications like “plant” or “animal”. In doing so, you will help other identifiers looking for plants or animals find that observation more easily. Without even one of those simple identifications, observations can sometimes get lost.

2. Sort randomly. If you go to the “Sort by” section, you will notice that the last option allows you to sort your search results into a random order. This is great for instances where you may not want an order to your observations for one reason or another.

3. Help add annotations. You can use the “Without Annotation” section to find observations missing annotations. As explained in TTT #1, annotations are important to include because they provide extra information for people who may be interested in using observations to look for patterns.

4. Assist newer users. Everyone needs a little extra help when they start out, both with identifying and understanding what should and should not be posted. By going to the section titled “Account Creation”, you can filter your search results by when a user’s account was created, allowing you to focus on observations created by folks who are new to iNaturalist.

Once you have the settings adjusted to your liking, click “Update Search”. To begin, click on the first observation that you want to identify. There are several ways to edit an identification. The most straightforward way to add a new identification is by clicking “Add ID” at the bottom of the page. If you agree with a provided identification, click “Agree” next to that person’s suggestion. You can also click “Comment” on the bottom of the page to add a new comment. If you look below the observation’s photo, you will notice boxes for marking “Captive/Cultivated” and “Reviewed”. If either of these apply, please select them. Remember, being a good identifier is about evaluating the whole observation, not just correcting its species name.

If you’re looking for a speedy way to edit an observation, then it’s time to check out the keyboard shortcuts. You can find these by clicking on the keyboard icon under the observation’s photo (bottom left-hand corner). Once you click it, a menu will pop up showing you all the different shortcuts available. For example, to add a new identification you can hit “i” and a new identification box will appear. Or, if you want to agree with the most recent identification, you can click “a”. Take a moment to browse through the options and try some out (when appropriate).

Now that you’re familiar with using shortcuts to edit identifications, turn your attention to the tabs across the top of the observation’s window and notice the four tabs (currently on “Info”). Next to that, you will notice a tab called “Suggestions”. This shows you the suggested identifications for this observation.

The next tab will show you the observation’s annotations. Remember earlier (in point number 3 above) when I mentioned how you can filter by observations without annotations? By using this tab, you can add annotations to observations that need them or agree/disagree with current annotations. You can do this by hand or use keyboard shortcuts to add new information. Click on the keyboard icon again and you will notice that the list has expanded to include new shortcuts. For example, when on the Annotation tab, you can add a “Female” notation by hitting “s” then “f”.

The final tab allows you to vet the data’s quality. Look through the checklist they provide and select “no” for any missing qualifications. This helps ensure that observations remain accurate.

Once you’re satisfied with your additions, you can get to the next observation by either clicking the arrow to the observation’s right side or hitting the right-facing arrow on your keyboard. No back buttons required! If you’re looking for a visual explanation of how Identify works, then check out this great video from iNaturalist’s help section.

TTT Task of the Week

Now that you’ve explored Identify, it’s time to put it to use! If there is a particular place or group of species that you usually identify, then try out Identify while continuing your normal identification routine. If you’re not comfortable adding new species identifications, try focusing instead on adding annotations. Go to your filters and set them up to find species without annotations. If you’re new to this feature, look for plants and animals with clear annotations, such as species of butterflies or flowering plants. By taking the time to add identifications and evaluate data quality, you will both be helping other users become better naturalists and ensuring that observations provide a reliable data source to those using them.

Thank you for helping us map Vermont’s biodiversity and happy observing!